How burnout stress affects our physical & mental health

This article is the first of a two-part series. Be sure to read part two, 10 Ways to Reduce Workplace Stress.

When I started my career as a healthcare professional almost thirty years ago, studying how our thoughts and emotions affect our health was one of my favourite topics. As a Registered Massage Therapist, I ran my own highly successful practice collaborating with medical doctors, physiotherapists, chiropractors, osteopaths and naturopaths. I also worked at St. Mary’s Hospital on a multidisciplinary team of medical professionals rehabilitating traumatic motor vehicle accidents survivors.

The role of a patient’s psychological state was evident in their health and recovery. Those with a robust support system felt loved and cared for, connected richly with their faith, and clung to hope tended to have better physical outcomes. Meanwhile, those who had little support felt disconnected from their family, friends, and faith, and those who had a primary negative bias regularly had poor outcomes. While this is not always the case, many medical professionals can attest to how a person’s cognitive and emotional state affects their stress levels, immunity, and physical health.

Burnout stress affects our health.

As a Burnout Prevention Strategist, I spend much time training C-level executives, managers, and employees to manage stress effectively to avoid burnout. I explain how overwhelming, unsuccessfully managed stress can lead to symptoms of burnout (1) affecting seven areas of wellness, including physical health, mental health, emotional health, spiritual health, relational health, financial health, and professional health. The manifestations of stress on the mind, body and emotions are significant.

This article intends to share how our cognitive and emotional reactions to stress directly affect our physical and mental health. Let’s get started.

What is psychoneuroimmunology?

Psychoneuroimmunology studies the relationship between immunity, the endocrine system (hormones such as cortisol and adrenalin), and the nervous system. 2 In short, Psychoneuroimmunology encompasses researching the effects of emotions on our health.

Important Terms

Neuroimmunomodulation is the interaction between the brain and the immune system.

Psychoneuroimmunology is the interaction between stress and the reaction of the brain and immune system to our psychological interpretation of events.

Psychoimmunology is the super system of interactions between the brain and immune system under our control by modifying our internal dialogue.

Challenges affect our thoughts, emotions & behaviours

There is a highly complex connection between our body and mind. Our physical body reflects how we react to life’s challenges through our thoughts, emotions, and behaviours. For the purpose of this article, the brain is the physical matter inside our skull. The mind is the totality of our brain, body, thoughts, and emotions.

Thoughts & emotions affect our minds.

In a sense, thoughts and emotions are the nutrition of our minds. We can intentionally change how we feel by creating positive thoughts. This does not mean telling ourselves lies, but rather, becoming curious and looking at things from a different perspective.

Emotions affect our physical state.

Feelings of fear, stress and anxiety often create a negative cognitive loop. In other words, just as our thoughts affect our emotions, our emotions can affect our thoughts. Both produce physical ramifications. For example, when we are worried or frustrated, we may experience neck tension, low back pain, headaches, or rapid breathing. In addition, our thoughts and emotions can affect many of our body systems, including our digestive, urinary, respiratory, cardiovascular, and endocrine systems.

Thoughts & emotions affect our immune system

Each thought and feeling we experience is accompanied by a shower of brain chemicals that affect and are affected by the billions of cells comprising our immune system. Our immune system is uniquely equipped with constant surveillance of intrusion and malfunction. It identifies invaders, compares them to a constantly updated memory bank, and prepares an appropriate defence. The immune system then attacks the intruder, defeats it, and cleans up after itself. Finally, the immune system updates its software with its latest learnings to prepare for future challenges.

The role of the immune system

The immune system functions in partnership with our cognition, emotions, and body. When we experience positive emotions, this partnership acts as a well-oiled machine. But when we experience a long-term onslaught of stressful thoughts, feelings, and physical reactions, it functions more like an army that has lost its general. As a result, the immune system may become overactive, underachieve, or even attack itself.

Immunity and stress

To be immune is not only to resist disease. Our immune system is meant to handle any stressor that comes our way. That is why positive stress, known as eustress, is beneficial. For example, when we have an exciting project we’re working on, this creates eustress, which causes a positive influx of adrenaline to help us complete the task. That’s a healthy response. The immune system is meant to strike a balance where it distinguishes between eustress that fosters positive growth and stress that wreaks havoc on our health.

Mind-body connection

The ancient Greeks believed in the mind-body connection. Socrates said, “As it is not proper to cure the eyes without the head, nor the head without the body, so neither is it proper to cure the body without the soul.”

The mind is a complex of innate capacities to associate, organize, and control the mind and body. The brain is a physical site where much of our physical activity is originated, moderated, and controlled via a complex system of nerves and hormones that comprise the nervous and endocrine systems.

Examples of the mind-body connection in modern medicine

Consider this. In the 1920s, Dr. Bruno Block was a famous wart doctor with his genius wart machine. 3 The machine took x-rays and painted each wart with brightly coloured “medicine.” He warned his patients not to touch or wash the medicine off until warts disappeared. One-third of his patients had their warts disappear after the first treatment.

It turns out the machine did nothing but offer the power of suggestion. The “medicine” was a simple food dye with no medicinal properties. Instead, the cure came from within the patient’s mind. The wart machine simply helped the patient believe that the wart could go away. 4

Here is another example. Studies show that patients who undergo general anesthesia can recall dialogue during their surgery. 5 The hypothesis suggests that the power of suggestion may play a significant role in post-operative patient recovery. Think of the implications of a surgeon who, while angry with his staff amid surgery, says, “You messed up! Oh well, the poor guy was a goner anyway”. Compare this to a surgeon that calmly says to the sleeping patient, “You are doing fantastic! You are going to be back on your feet in no time.” There is a reason nurses are taught to offer encouragement to patients far beyond boosting morale.

Neuroanatomy 101

Let’s take a quick lesson in brain anatomy. We will focus on just two main areas of the brain: the Limbic System located deep within the brainstem and the Frontal Lobe, situated at the very front, top of the brain below the forehead.

Survival: the limbic system

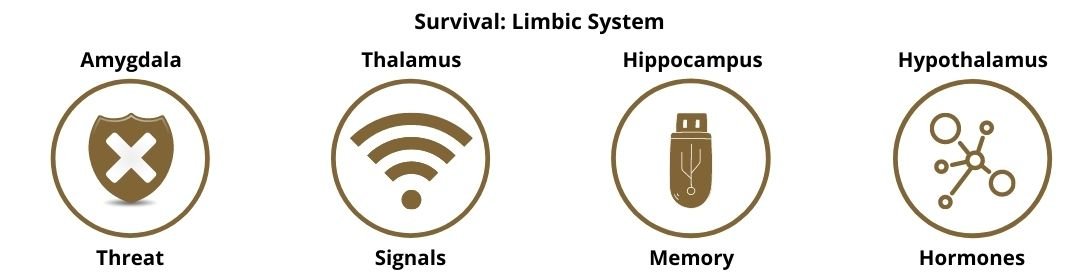

The limbic system comprises several parts of the brain:

The amygdala is responsible for detecting and responding to fearful and threatening stimuli.

The thalamus is responsible for sensory and motor signals, consciousness and alertness.

The hippocampus is responsible for learning, memory, and recognition of enjoyment.

The hypothalamus is responsible for controlling the endocrine system, including hormones and glands.

The limbic system has an incredible potential to control our immune system cells. Understanding the roles of our limbic system allows us to turn that potential into reality. Then we may experience the wealth of an unimaginably efficient internal apothecary.

Think of the limbic system as the intensive care unit of the nervous system. Its functions can be categorized by Five F’s: Fight, Flight, Freeze, Feed, and Fertilize (reproduction). In other words, it is focused entirely on survival.

Stress causes us to have thoughts that create an emotional response, triggering our amygdala to produce physical manifestations such as rapid heartbeat, pumping blood away from our digestive tract to our muscles, and muscle tension. Equally as important, when we are calm, our amygdala does not fire, and a different set of hormones flow through our blood. For example, oxytocin is a hormone responsible for connection and trust which flows only when the amygdala is not triggered.

Higher thinking: frontal lobes

The frontal lobes are part of the brain's outer surface called the cerebral cortex. They are located at the very top and front of our brain, beneath our forehead. This is where our higher thinking happens. It is responsible for executive functioning, problem-solving, decision-making, conscious thought and empathy. This is where we want to spend most of our time when working on a project, sitting around a boardroom table, writing code, or having a meaningful conversation with a loved one.

The limbic system hijacks the frontal lobes

When we experience stress, it triggers our amygdala within our limbic system. This immediately puts us into a fight, flight, or freeze response. The amygdala responds instantaneously, more quickly than our frontal lobes, causing us to go into a reactionary response rather than thinking mode. Essentially, the fight, flight or freeze effect of the amygdala highjacks our rational thinking frontal lobes in the name of survival.

At the same time, the amygdala, through a complex pathway, tells our adrenal glands, which sit on top of our kidneys, to pump out the hormones cortisol and adrenaline. These hormones create a cascade of events within our body, such as rapid heartbeat, increased blood pressure, decreased digestion, and sweating, all of which prepare us for fight, flight, or freeze.

This response is essential when a bear is chasing us, and we need to get to safety immediately. But when stress triggers this reaction dozens or even hundreds of times a day, we move into chronic stress and the unhealthy state of languishing. In this scenario, our amygdala can become over-reactive, and we may react far too often from our survival mode rather than from our problem-solving, decision-making, empathetic abilities.

There is no question that stress affects our physical, emotional, and mental health and immunity. So what can we do about it?

How to overcome stress

It is vital we learn effective stress management strategies for overcoming stress and building resilience so that we do not face burnout. Though we cannot change the stressful circumstances we encounter, we can change our thoughts, which in turn change our emotions and effectively stop the stress cycle.

Read the next blog for practical stress management so you can overcome stress, build resilience, and prevent burnout.

Sign up to receive future blogs directly to your inbox so you can thrive in you personal and professional life.

About the author

Bonita Eby is a Burnout Prevention & Organizational Culture Consultant, Executive Coach, and owner of Breakthrough Personal & Professional Development Inc., specializing in burnout prevention and wellness for organizations and individuals. Bonita is on a mission to end burnout. Get your free Burnout Assessment today.

References:

World Health Organization. (2019, May 28). Burn-out an "Occupational phenomenon": International Classification of Diseases. World Health Organization. Retrieved December 14, 2021, from https://www.who.int/news/item/28-05-2019-burn-out-an-occupational-phenomenon-international-classification-of-diseases

Tausk F, Elenkov I, Moynihan J. Psychoneuroimmunology. Dermatol Ther. 2008 Jan-Feb;21(1):22-31. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2008.00166.x. PMID: 18318882. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18318882/

Block, Bruno: Klinische Wochenschrift VI: 1927, 2271, 2320.

Perlman, H. H. (n.d.). The Innocent Wart. Clinical Pediatrics, 2(5), 238–246. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/000992286300200508

M. M. Ghoneim, Richard B. Weiskopf; Awareness during Anesthesia. Anesthesiology 2000; 92:597 doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/00000542-200002000-00043. https://pubs.asahq.org/anesthesiology/article/92/2/597/38147/Awareness-during-Anesthesia